One of the finest Japanese restaurants in the Netherlands is tucked away in a corner of a Japanese fish factory, located in the industrial harbor area of IJmuiden—essentially Amsterdam’s port. The restaurant is called Hokkai Kitchen, and both it and the factory share a logo featuring a horse mackerel, known in Japanese as aji.

Inside the restaurant, subtle Japanese decorations have been added, yet it’s still clear you’re in the corner of a fish factory. This contrast creates a fascinating atmosphere—where the understated simplicity of the setting and the dishes is beautifully balanced by the exceptional quality of the food and service. The restaurant offers a 5 course chef’s menu (omakase is the Japanese word for that) for 100 euros as well as à la carte—mostly sushi. The sake pairing with the omakase is 60 euros for 5 glasses.

Not to mention the exceptional quality of the sake pairing, curated by Menno Tol—the only Master Sake Sommelier in the Netherlands. Hailing from Volendam, his surname alone would give that away to most Dutch people. On one hand, it makes perfect sense that he works here, given Volendam’s deep-rooted fishing heritage. On the other hand, it’s not exactly what you’d expect from someone from Volendam, which adds a delightful twist to his story.

I had the pleasure of meeting Menno and experiencing his remarkable expertise in sake and food pairing during his time at the Michelin-starred Yamazato restaurant in the Okura Hotel in Amsterdam (read more about that here). Sadly, he wasn’t present at Hokkai Kitchen during our visit, but Rosanna stepped in admirably and ensured the sake experience was still top-notch.

Hokkai Kitchen is incredibly popular, so reservations need to be made weeks in advance. When we arrived, our table wasn’t quite ready yet. While we waited, we were offered a small treat: a sample of crispy seaweed on rice. A simple gesture, but a very tasty one—and a promising start to the evening.

Once we were seated, Rosanna came to our table with a warm welcome and passed along Menno’s regards. As a special gesture, she poured us a sparkling sake—Izumibashi—courtesy of Menno. This sake is made sparkling through a second fermentation in the bottle, with the yeast left in, giving it a cloudy appearance after Rosanna gently shook it before serving. The flavor was beautifully fruity and well-balanced, with notes of lychee, complemented by a creamy texture and a clean, soft finish. It was a delightful and refreshing start to the evening.

The amuse bouche of mackerel tempura was served with this, a very nice pairing.

In addition to the omakase, we ordered a special dish: Dutch salted herring, lightly smoked and served with seaweed and pickled daikon. The herring had a delicate, creamy flavor and was incredibly tender—an elegant twist on a traditional Dutch ingredient. The richness of the fish was beautifully offset by the crunch of the seaweed and the tangy brightness of the pickles.

The sake served with the herring was Tatsu Orange Label No. 3, a yamahai-type sake—naturally brewed using ambient lactic acid and aged for three years. This style gives the sake a rich, complex character with pronounced umami. It had a distinctive aroma reminiscent of aged cheese, which might sound surprising but worked beautifully with the lightly smoked Dutch herring.

Rosanna explained that one of the key factors distinguishing different types of sake is the degree to which the rice grains are polished. She showed us samples of rice with varying polishing levels: one where 45% of the grain had been removed, resulting in a sake that’s elegant and fruity, and another where only 10% had been polished away, producing a heartier, more robust flavor profile. In general, the more the rice is polished, the more refined and delicate the sake becomes.

Next came the sashimi cocktail, the chef’s signature dish. It featured an exquisite selection of tuna, salmon, and hamachi, served with a soy-based sauce, a chiffonade of shiso leaf, and a striking addition: an egg yolk that had been flash-frozen to -80°C (-112°F). This technique gave the yolk an exceptionally creamy texture, adding richness to the dish. The fish was incredibly fresh and tender, and the combination of flavors and textures made this course truly outstanding.

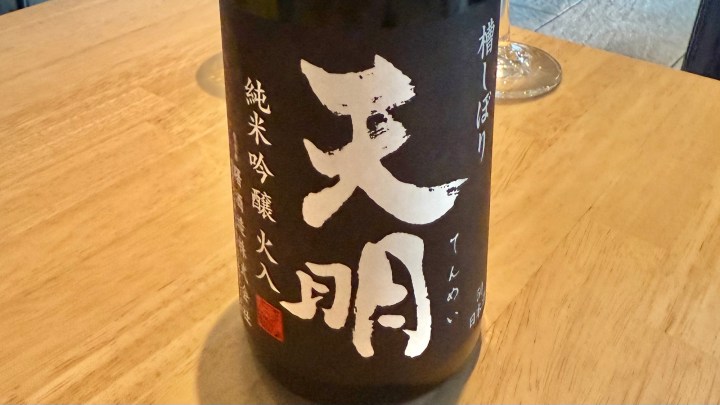

The sake paired with the sashimi was the Funashibori Junmai Hiire Orange no Tenmei, brewed by Akebono Shuzo in Fukushima. This junmai-style sake had a crisp flavor and subtle citrus-like aroma and was an excellent pairing.

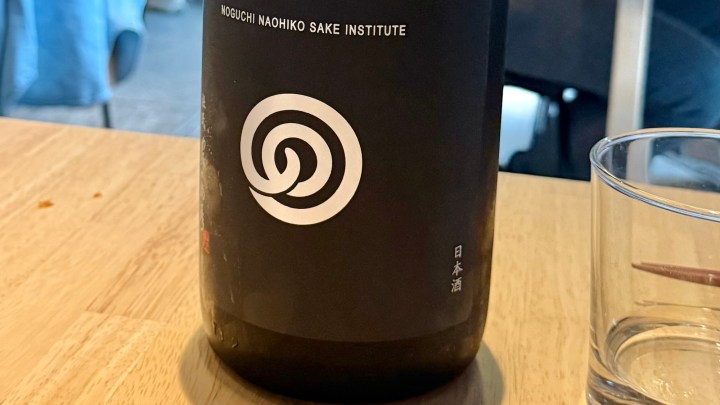

The next sake was the Honjozo Muroka Namagenshu by the Noguchi Naohiko Sake Sake Institute, made from rice polished to 60% and aged for over 18 months. It had a crisp flavor and aroma, and had been chosen to cut through the richness of the grilled fish in the next course.

The yakimono course featured three types of grilled fish: horse mackerel, regular mackerel, and black cod marinated in miso. The horse mackerel was served in a traditional style as a whole fish, which added authenticity but also made it a bit challenging to eat due to the many small bones. The black cod with miso—a well-known and beloved combination—was executed beautifully, with the rich, buttery texture of the cod complementing the sweet-savory miso marinade. While the fish was well-prepared, this course was probably our least favorite of the meal, perhaps because it lacked the finesse and surprise of the earlier dishes.

The next sake was the Kanadel Pizzicato Sake by Manotsuru. This sake was slightly sparkling due to a gentle secondary fermentation—hence the name “Pizzicato.”

This was a good pairing for the trio of nigiri: sea bass, squid, and Dutch salted herring. The nigiri was excellent. The rice was served lukewarm and had a pleasantly firm texture—what I would describe as al dente. It was only lightly seasoned with sushi vinegar, allowing the flavor of the fish to shine. The rice base was loosely packed, holding together just enough without being compressed, giving the sushi a delicate, airy feel. Dutch salted herring is, of course, not a traditional sushi ingredient. While unconventional, it was seamlessly integrated into the menu, showing how Japanese culinary techniques can adapt to regional specialties without compromising on quality or harmony.

The next sake was simply called Jam, made by Haccoba—a craft sake brewery in Fukushima. It’s brewed from rice polished by only 10–12%, and includes elderflower as an added ingredient. This gives it a muscat-like aroma, with a sweet and sour flavor profile from the combination of yellow and white malted rice. Rosanna explained that in Japan, it’s only legally permitted to start a sake brewery in a building that has historically been a sake brewery. As a result, younger brewers often turn to crafting experimental styles of sake using non-traditional ingredients. Because of these additions, Jam isn’t officially classified as sake.

It was a well-chosen pairing for the snow crab temaki with salmon roe. The freshly made pickled ginger and wasabi—so much more vibrant than the pre-packaged versions—made all the difference.

The next sake made its pairing intentions clear from the start—it featured a picture of a tuna on the label. This was Komaizumi Maguro Ginjo-shu, a sake specifically designed to complement tuna dishes. Brewed from rice polished to 60%, it has a flavor profile rich in umami with a clean, dry finish.

And so this was the perfect pairing for the next course: five different types of tuna nigiri. These included lean tuna, medium-fatty tuna, fatty tuna, soy-marinated tuna, and tuna tartare. Each piece showcased a different texture and flavor profile of tuna, and the sake’s strong umami character with its dry finish complemented the richness and variety beautifully.

Some of the sakes were served in glasses resembling small wine glasses, while others came in traditional ceramic cups, often accompanied by beautifully crafted serving vessels for top-ups. In Japan, it’s considered impolite to pour sake for yourself—so we took turns serving each other. The choice of glassware also subtly reflected the character of each sake: more aromatic or delicate sakes were served in stemmed glasses to enhance the nose, while richer, more traditional styles were poured into ceramic cups to emphasize texture.

This marked the end of the omakase, but we decided to add an extra course: wagyu beef. To accompany it, Rosanna brought out Takehanoyuki, a Tokubetsu Junmai-shu sake. Made from rice polished to 60%, its standout feature was that it had been aged in barrels, giving it a smooth, nutty character with rich umami and a creamy texture.

The wagyu was served as nigiri, which was finished by the chef table-side, by charring the wagyu with a red hot piece of charcoal. This produced a nice smoky flavor, which was enhanced by a teriyaki-like sauce that was subsequently brushed on top of the wagyu. It was served on your hand on a sheet of nori and a dollop of fresh wasabi on top.

The wagyu was served as nigiri, and finished table-side by the chef. A red-hot piece of charcoal was used to lightly char the beef, releasing a smoky aroma that instantly elevated the dish. A teriyaki-like sauce was then brushed over the wagyu, adding a sweet-savory glaze that complemented the meat’s richness. The nigiri was presented directly on the hand, laid on a crisp sheet of nori with a small dollop of freshly grated wasabi on top.

To finish, I ordered the chef’s dessert—curious to see how Japanese cuisine, which isn’t typically known for its sweets, would approach it. The custard was a bit bland and understated, but the nashi pear marinated in yuzu juice, topped with a chiffonade of shiso leaf, was very nice.

We had a wonderful dinner at Hokkai Kitchen. Foodwise it is mostly a sushi restaurant, because the sushi (and sashimi!) dishes is where the kitchen shines. Complementing the food is an impressive selection of sake, expertly curated by knowledgeable sommeliers who are happy to guide you through pairings that elevate the entire experience. The attentive, friendly, and knowledgeable service is another highlight, more akin to what you’d expect at a fine dining restaurant than in the corner of a fish factory. Prices are surprisingly reasonable given the caliber of the food and service, which explains why reservations are essential and often need to be made well in advance. I’m already looking forward to my next visit—the only downside is that I’ll need to find a designated driver, as IJmuiden doesn’t have a train station. Or come by boat again, as the restaurant is within walking distance from the IJmuiden marina.

What an absolutely fascinating meal . . . I have been to Japan dozens of times on business and private trips and thought I knew my sakes and my dishes and every which way fresh fish could be served . . . looking at your experience I suddenly feel I know very little . . . 🙂 ! Oh, how I wish I could have that tasting plate of tuna nigiri to see how my palate would differentiate! Being me and female methinks I would have passed on the beef and kept the experience totally fishy, but . . . thank you for sharing this one . . .

LikeLiked by 1 person

The wagyu was the only non-fish item on the menu. First time I’ve had wagyu served as nigiri.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What an amazing meal! Everything looks exquisite. I’ve been to a sake tasting, but not like your experience. And very interesting information about sake.

LikeLiked by 1 person

In Italia i ristoranti giapponesi sono pessimi, complimenti agli olandesi per averne uno eccezionale!

LikeLiked by 1 person